Mercatus, a digital engagement provider that builds mobile apps and websites for grocery retailers, says the near-instant move to curbside and delivery at grocery stores has created major challenges for the industry that mirror the restaurant delivery space: limited staffing, a strained supply chain and tension between stores and national delivery providers like Instacart that are straining under the stress of a newly digitized grocery business.

Mercatus President and CEO Sylvain Perrier said it’s “reasonable to think” that a portion of independent grocers could be forced to close, whether that’s from basic staffing shortages, increased costs to enable delivery and pick-up orders, as well as the challenges for brands that, in some cases, have had to use their own employees to fulfill third-party orders from Instacart and other online grocery delivery brands.

“It’s very difficult to sustain operations in a way that’s considered safe and profitable in these atypical times,” Perrier said, underscoring the seriousness of the challenge that most consumers aren’t aware of in such a busy, prolonged news cycle. “It’s not a question of economics anymore, it’s a question of survival.”

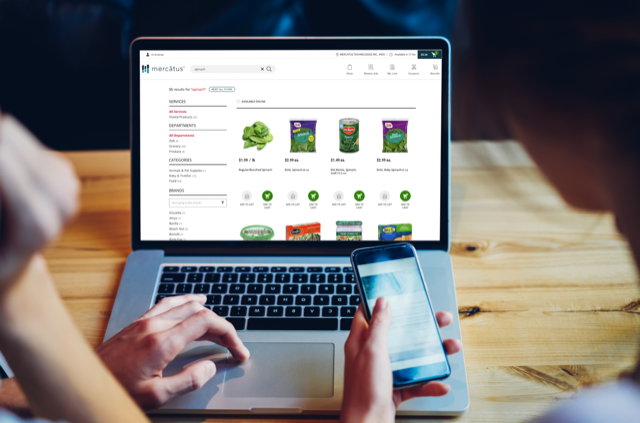

Originally started as a “hardware play” that transitioned toward digital engagement, mobile apps, websites and digital commerce functionality, Mercatus helps grocery clients integrate with approximately 55 different third-party solutions that include point of sale, loyalty, payments and marketing.

As its call volume spiked the day the COVID-19 crisis was officially deemed a pandemic, the Toronto-based provider has seen a huge spike in traffic and incoming calls that has persisted as cracks appear in the infrastructure that was suddenly tasked with immediately feeding many more people, as restaurant dining rooms closed or were restricted in the subsequent weeks.

While mega grocery retailers like Walmart and Costco will likely be fine, even as they restrict the number of shoppers that can be allowed inside at a given time, Perrier sees smaller, independent grocers as bearing the brunt of the challenges in the industry.

“These two retailers have extremely mature click-and-collect and delivery capabilities, and it would not be very difficult for them to convert” to off-premises operations, he added. Even with more business than ever, he said “core sales are going up for grocery retailers, costs will go up equally, because they’re bonusing their currently employees or they’ve increased their hourly wages, and they’re spending more time clearing their stores—the trickle-down effect to the bottom line will probably be minimal at best.”

As third-party grocery delivery brands gobble up a much larger share of the sales, retailers are buckling under the stress of packing orders for third-party brands, even as Instacart has hired hundreds of thousands of additional “pickers” in recent months.

“They’ve started to significantly reconsider their partnerships, because it’s not a partnership,” Perrier said. “Instacart does not have enough people to fulfill deliveries, and it’s putting an immense amount of pressure on them ..and even more so on the consumers.”

Adding that Instacart’s “survivability becomes very questionable” for a variety of reasons, Perrier said the pandemic’s impact on customer behavior has meant that projections originally slated for 2025 in the grocery industry are being reached already as customers utilize off-premises channels far more than in recent years.

According to current industry stats, approximately 28 percent of North American grocery transactions have migrated online, with 65 percent of those shoppers now exclusively buying groceries online, Perrier said.

For many retailers, that means their “best basket” has moved online, even though supply chain issues mean that shoppers are facing shortages, protein rationing and other dynamics that have put a cap on sales growth, and therefore profits, for many grocery retailers.

It’s not just younger, tech-savvy shoppers morphing into click-and-collect consumers. In talks with clients, Mercatus has found that even elderly shoppers with iPads and laptops are coming into the online grocery fold, which Perrier said is a great opportunity for grocery brands to consider reinventing themselves with many of these recent industry shifts expected to last beyond the crisis.

“You hear the argument that this is a millennial’s world or it’s partially a Gen X world, but the reality is, in the last 12 months, we’ve seen the above-65 [consumers] catch up—that’s why we can confidently say the distribution is very equal.”

Perrier added that these numbers include customers who are over-75 crowd, as well. To aid older shoppers and those new to online channels, many grocery brands have added specific help desks to assist shoppers navigate ordering sites and build their shopping baskets.

As the impacts from the pandemic persist, and move from big cities into more rural areas, Mercatus sees a greater number of smaller, independent grocers struggling to fulfill demand and keep their doors open. Some retailers are even allowing shoppers to email grocery orders to the store, which would then be packed and prepared by the store’s employees.

Looking ahead, Perrier said it’s reasonable to expect additional challenges for retailers in less affluent areas, partially because government SNAP assistance programs don’t cover delivery costs.

As these situations unfold with time, he stressed that the problem is not with the supply chain, but inside the actual stores trying to change their business models on a dime.

“It’s not that we don’t have the raw materials to manufacture, it’s not that we don’t have the manpower or capabilities to do it,” he said. “It’s just a question of time.”